| O Ce Biel | ||

| From the Friulan song "O Ce Biel Cjiscjel a Udin" | ||

| Memories of 1970s Friuli | ||

|

|

||

| HomeArrivalBrandoGowanTalmassonsTerremoto | ||

| ReturnFoodPoemsSongsVeniceTriesteUdineseMerlot | ||

Arrival |

||

We all had stories of our first few days in Friuli. There well may be overlap, always likely as we were taking similar steps in our lives, but it seems better to include them in full rather than editing, otherwise some detail might be missed. There are two accounts here from me and Chris Taylor. |

||

Charlie |

||

|

||

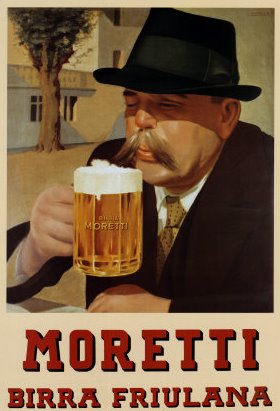

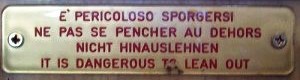

The famous words of warning, the first time I saw them below the window of my railway carriage between Milan and Venice on Saturday 22nd November 1975. They've stayed with me ever since, a four-language metaphor for the perils of life. I was heading east, bound for the city of Udine, capital of the Friuli region in the north-east of Italy. It was mid-afternoon, chill and grey outside, darkening towards nightfall. The terrain was flat, populated irregularly with farmhouses and factories, modern suburbs of apartment blocks as we slowed towards each station. We arrived at Mestre at about 5pm, where I got off to change for the Udine train. Mestre station. Concrete, angular, grey, cold, windswept. Nothing remotely welcoming. The words had been forming in my head for some hours: "What have I done?" This really didn't look like the Italy of the travel brochures, great cinema or my imagination. Two hours later I was in Udine. Same railway architecture. The only difference was the throng of army conscripts in grey-green uniform, perhaps returning from leave; Udine was a major centre for military service. I walked out of the station and looked up and down the street, itself dark and unfriendly with modern housing blocks set above commercial premises. I had no idea what I should do next. Six days earlier I had been living in a squat in Burton Street, London WC1, at the top end of Bloomsbury just south of the Euston Road. Sue Boardman had lived in the house next door before going to Udine to teach English in October. She called me. Or did she? We didn't have telephones in the houses, mobiles didn't exist. Did she send a letter? Perhaps it was a telegram. Anyway, she said that they needed more teachers at the Udine Oxford School of English and that I should speak to Gowan Hall, director of the group. I duly rang him, encountered little interview rigour and was engaged for the following Monday. A flurry of activity, including resigning from my van-driving job and taking my few possessions to my parents' house in Worcester, and I caught the train from Victoria on Friday. I stood outside Udine station with few contact options. The school was closed for the weekend. I didn't know where all the other Oxford School teachers were. I didn't know where Sue lived. Opposite the station was the austere Hotel Europa. I crossed the road and checked in. A miserable grey-green first-floor room, bed, desk and not much else. I've never been one to hang out in hotels. After unpacking my clothes, I went downstairs and into the street. I followed the signs north to the city centre. After ten minutes, modern blocks gave way to older classical buildings, my gloom lifting as functional concrete gave way to stone townhouse "palazzi", cobbled roads and marble pavements. I walked under ancient porticos and arrived in Piazza della Libertą below the castle. "Much better", I thought. I followed the gracious curve of Via Mercatovecchio, the main street, colonnades on both sides, elegant clothes shops.  It was very quiet for the middle of town on a Saturday night and I was concerned about finding somewhere to eat. Mercatovecchio offered nothing and I hadn't yet discovered the side streets that hid the traditional "osterie", snug and convivial watering holes. I walked out of the top of Mercatovecchio, round the corner into a little square, and there was a simple pizzeria. I went in and ordered pizza and a pint of Birra Moretti, the local brew according to the waiter. I hadn't yet seen the illuminated iconic image of Moretti Man on the north side of town, replicated on bottles and bar fronts everywhere:

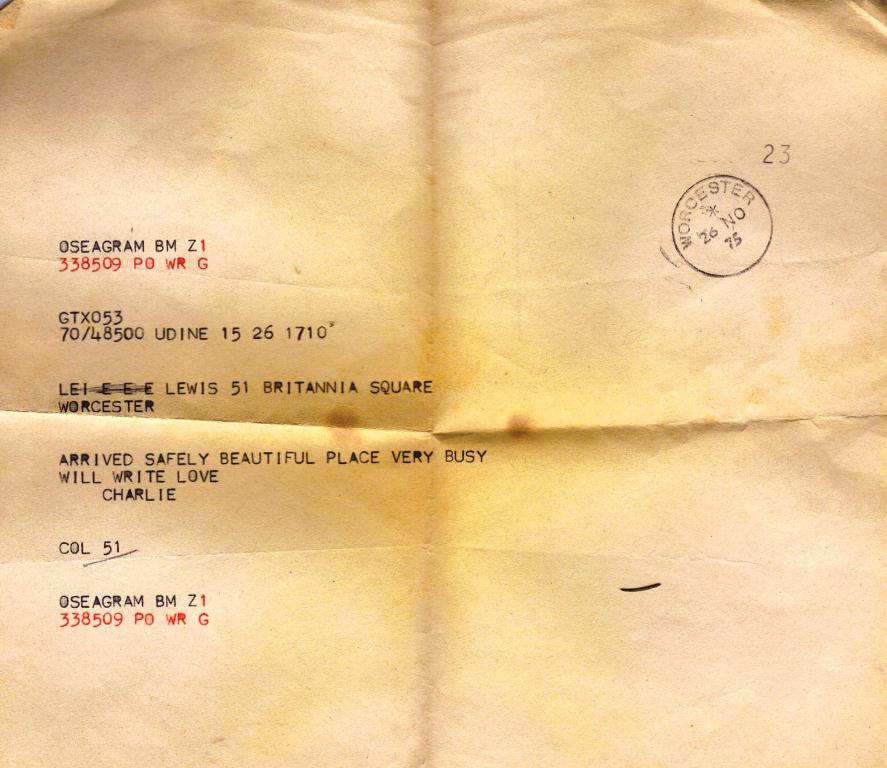

This picture is important. He's not Italian, is he? More Teutonic, a man you might expect to find sitting outside a bar in Munich. He's drinking beer, not the wine we associate with Italy. There you find a big pointer to the characteristics of Friuli and the Friulani. I came to understand that they - or their stereotype - had a strong pull to the Germanic north and a disdain for the qualities of Rome. They belonged to a culture of hard work and honesty and viewed the south of Italy as lazy, corrupt and licentious. This belief bordered on racist. But it also had substance in the way they lived. Tough people leading a decent life on tough terrain. Fortified by the beer and pizza, I returned to the grim Europa and managed a decent sleep. The next few days are a blur. I met up with Sue, and with Terry Chamberlain the school director, and his wife Ren. On Sunday evening there was a party somewhere in the hills where the Oxford School teachers were guests of an Italian student's family. I met Chris Taylor and Charles Thompson that night. I didn't know it then, but Sue, Chris, Charles and I would become firm friends, a pack of four roaming loose around the villages of Friuli, journeys of exploration that always seemed to finish at an "osteria". I moved into Sue's flat, as her roommate Fausta was setting up elsewhere with her man, Andrew. It was a terrible place, described more fully in the "Brando" section, but it was cheap. I had to go to the police Questura to obtain a residence permit, where I was served by a very sombre official. He typed up my details on a manual typewriter of industrial proportions, one finger at a time. At one point I asked him (it must have been in English) if there were many British in Udine. Pause ... clunk ... pause ... then he said, "Enough." I managed to get a telegram of reassurance off to my parents. Here it is, discovered among my mother's effects when I was clearing up her flat after she died. I'm amused by the difficulty we had with my surname. It must have been the "w", as it's not in the Italian alphabet. I often had to settle for Levis.

I was indeed very busy. The first few weeks up to Christmas were not much fun. I'd arrived several weeks after the others, who had already cut their teeth on the twin challenges of teaching English and learning Italian. My timetable was full and consisted exclusively of beginners' classes, as the more advanced had been taken. The school licensed a truly dull textbook called the British Rapid Method from a school in Rome. Each chapter was built around a topic such as going to the beach, with the grammar woven in behind the scenes. No Italian was to be used - which I couldn't speak anyway - and the students on day one had little or no English. Large placard-sized flash cards depicting enlargements of the pictures in the students' books. Lots of repetition and drilling. For two hours at a time. The only thing that had a chance of being rapid was my losing the will to live. All the courses running at the school in the lovely city centre had also gone. I was assigned to offsite teaching in offices and factories, usually accompanied by a bus ride. There was one silver lining, the village of Talmassons. There's more on that in a separate section. |

||

Chris |

||

Teaching Geography and Economics at Chingford High School was alright, I suppose, but living in a dingy flat in the East End in what is euphemistically called a 'fraught relationship' was less so. I was looking for a way out and it was fashionable then, in the mid-seventies, to take a year abroad. Unbelievably it was then possible to do this and come back and find your job still there, or something similar. That didn't last long. Anyway I applied for jobs across the European Union, though I think it was still called the Common Market back then, and all of them in the English teaching sector. What a passport that was to some carefree time in Europe for hundreds of very differently qualified youngsters. I got accepted for interview for jobs in Germany, Spain and north-east Italy. I don't remember where the German and Spanish posts were but the former didn't want me and I didn't want the latter. In the first case the panel decided that the basic German they thought necessary for new teachers went beyond my collection of half a dozen vocabulary items. In the second case I was put off by the fact that they wanted me to work till 10.00 pm every night. Little did I know then that this was the hour when Spaniards only started thinking about dinner and evening entertainment. And so north-east Italy it was, and specifically the Oxford School of English. I was interviewed, in the Waldorf Astoria, by Gowan, who will figure extensively in this account. He was charming, witty and very definitely gave me the impression that I had got the job. The post would be, he told me, in Udine. This might have led many candidates to react with 'Where?!' and reconsider their options, but through one of those weird coincidences in life, my father had been stationed in Udine at the end of the Second World War while he was a REME mechanic following the slow trek home of the British Army. He always called it 'Yudeenee' but I worked out we were talking about the same place. He hadn't been abroad since till he came back a year or two after I arrived to tread old paths. There was however, a further formality to go through; I had to have a second interview with the urbane (or creepy) owner of the organisation I was going to work for, a gentleman who rejoiced in the name of Richard Creese-Parsons. He conducted this interview in a borrowed flat in Hampstead or Highgate or Harrow, I don't remember. Anyway the next time I saw him was on our introductory training course in Venice. It was September 1975, Britain was falling slowly but surely into some sort of economic stupor, or "growing old graciously" as I heard it put. I had arranged to travel down to north-east Italy with a girl who was starting in the same job as me in Padua. It was a long drive in her little car and we stopped for the night in a small back street pension in Rheims. The next morning we discovered that my suitcase had been stolen from the boot of the car. This meant that I arrived for my new career with what I had in a small overnight bag. Not the most auspicious start, but made worse by the policeman who took our report. "Ah, les tziganes!" he said, referring to the gypsy population who hit town at that time of year to pick the champagne grapes. A few years later in Provence, after a similar episode of breaking and entering my car, a similar flic said "Ah, les marocains!" And then he asked us where we were headed. "En Italie", we offered. "Ohhh, be careful when you get there!" Prat! And so we arrived in Udine late one afternoon in late September, the girl having been generous enough to bring me all the way and then go, effectively back, to Padua. This generosity did not stretch, however, to claiming the insurance for my stolen stuff - it would affect her no-claims bonus! So I found the Oxford School, and Terry Chamberlain, the director, welcomed me and suggested I go eat in a place called the "Pappagallo". I would return to this rather uninspiring parrot-named establishment many times in the following years - it is now a sort of cocktail bar and I haven't been for ages. I was effectively the first to arrive in via Paola Sarpi, to be followed shortly after by a bloke called Charles and later that evening by a girl named Sue (pace Johnny Cash). We all had to kip down in the staff room, though the next day I was found digs in via San Martino where, said the landlady, a certain "Andrea" had lived the year before. This "Andrew" would reappear in Udine after a couple of months and became one of the gang, or at least on the fringes of it. However, the more immediately interesting character to appear on the scene that first day was Don, an American from "upstate New York" who had been working for the School for a year or so. It was he who first introduced us to the delights of the Friuli wine industry, and he became a firm friend even though he went back to the States at the end of the year to marry Sarah and after that we would see each other roughly every five or ten years on one side or the other of the Atlantic. Sadly Don died this year in California. The first bar crawl that Don took us on already targeted many of the watering-holes we would come to love and frequent in the years to come, first among these was "Brando's" in Piazzale Cella, though the "Marinaio" and the "Fornaretto" would also figure largely and are covered in more detail elsewhere. Another place we ended up frequenting with a certain regularity was "Ivo's". This was a most unprepossessing place tucked away in a square in the centre which Gowan (our most regular contact with the Oxford School hierarchy in Venice and who became a mate to all of us) had somehow discovered and recommended. The place was run by Ivo and his long-suffering wife and the clientele were mostly drunks or thereabouts. In later years Ivo would lose his marbles and the place became history. But this was Udine. On the second day of this adventure (it still was an adventure and would remain so for some time until it dawned on us that this was real life) the afore-mentioned Gowan arrived in his elderly Jaguar and carted us off (me, Charles, Don) to "the country". This was Friuli, which I must admit I had never heard of, let alone that it was an autonomous region allied with Trieste, the old Habsburg city on the eastern edge of what was still Western Europe. Anyway the first port of call was "da Ridolf" in Nimis, a small town. This was a totally new experience, an old bar in a beautiful courtyard selling wine (and wine), very different from an English country pub. In the months to come many more small towns, villages, and wayside inns would be discovered until Friuli became a place we could identify with and where we were generally welcomed warmly (not ecstatically, it isn't Naples!). Before beginning work, we all went down to Venice for the induction course and met our new colleagues from all the other Oxford Schools in the north-east of Italy, which was as far as the franchise reached. So there were new teachers from Padua, Verona, Treviso, Venice itself and so on, including a place nobody had heard of called Pordenone. The only representative of this industrial city (famous for washing machines) was a long-haired, Woodbine-smoking Yorkshireman called Mick. Mick is still in Pordenone as I am still in Udine (obstinate buggers these Yorkshire types) and we've been mates for all this time. Other folk from those days who are still around include Peter Mead, who was based in Verona, now interpreter for NATO in Rome, and Pat Knipe, a rather taciturn ex-seaman from New Zealand who is retired from various jobs around the Venice area. I see them all, though infrequently. The afore-mentioned induction course was organized by the creepy Creese-Parsons, with the good guy Gowan in the background. The principal instructor was an Australian woman who took us through the dynamics of the British Rapid Method. This was all very new and, at the time, seemed revolutionary and exciting. Now it has been ridiculed as critics query the usefulness of saying "This is a book" when no English speaking person would ever say it. Similarly, learning expressions like "I am opening the door" find few practical outlets. However, more disturbing than this, I later realised, was the linguistic ignorance displayed by these prospective language teachers. "What the hell's the Saxon genitive?" "What's a relative clause when it's at home?" Unfortunately this led to embarrassment when it transpired that many Italians knew these things, even though they couldn't get a correct sentence out. This situation has progressively worsened as the British education system has removed the teaching of grammar, and foreign language teaching has been relegated to an irrelevance. We on the front line in the universities see this in the appalling levels of UK Erasmus students coming to study Italian. But I digress. The course went off OK, we had a few nice meals, arrangements were made to meet up with some of the new colleagues - Mick, and some of the Treviso and Verona crowd. There were others I was thankful never to see again. And so back to Udine and the beginning of term. |